Peregrini. The Garvellachs. 2024

- pengodber

- May 3, 2025

- 22 min read

Updated: May 4, 2025

St Brendan the Navigator. Patron Saint of those who wander the seaways with curiosity.

July 15th 2015. The best day of my life so far. A thrilling mix of bacon, coffee and diesel fumes assaults us as we lean over the Calmac ferry rail. I'm trying to look like I've done it all before. Only I haven't. We’re chugging out from the jetty in an easy curve. The harbour mistress is already pulling off her day viz jacket and heading back to the farm.

In 2015 I am sixty five. I’ve only just begun. I’ve just kayaked round Colonsay and Oronsay with a band of heroes. There were big wavey bits where I heard an Irish Coast Guard talking over my sparky new VHF radio! We were that close to Belfast! There were rock alleyways with water as still and clear as air. The secret lives of crabs were on display jsy for us, our sleek hulls suspended a few feet above them.

I’m old and I’m a total novice but this is something my companions don’t seem to have noticed. Nobody’s mentioned it anyway. My sea kayak looks cool loaded up with the others on top of Roger’s tidy van parked down in the hold. A man and a woman had walked their kayaks on. This ferry is for Oban. Will that be the end of the journey for them or will they be paddling on for new adventures? I’m almost sick with envy.

I have entered a brave new world where CalMac breakfasts are the beginning and end of great adventures. The smell of bacon and coffee fills the air. Through the big smeary, square windows Alan, his daughter Victoria, Roger and I have a salted view of a parade of magic islands.

“That’s the Garvellachs,” says Roger gesturing to our right. (On the port side about 12 nautical miles away don’tcha know.) “We ought to get Pen there don’t you think Alan. You’d love it”. You mean I can come again! I didn’t slow you up? It was okay that it took me half an hour to decide where to put my tent and one wee nip of whisky leaves me witless?

A magical conversation flows straight through my heart of the Correyveckan (I’ll pass on that one), the Grey Dogs (that one too) and of the Garvellachs, The Rough Islands, the Islands of the Sea. Above everything I want to go there, I want to be there, but most of all I am so happy because I know I’m ok, I'm accepted. If these people noticed I’m 65 and a total newcomer they didn’t mind. I’m ok by them. This may be the happiest day of my whole life so far.

The thing about sea kayaking is that your boat is tiny, it is “you” sized. It’s yours in the way that your first bike was. You can skim with the great ocean flow. You are part of the electric energy of the waves. You can slide up the mass of the rocky shore with an explosion of sea bubbles or slip into tiny gullies that no other boat could make. And you can carry everything you need in your hold. I’ve wanted to be doing this since I was 14, and now I have the chance. Work commitments and family commitments are no longer the air I breathe. It’s expensive but do-able. Kind people like Alan and Roger are holding open the doors. Heaven’s doors are open.

Amy on wave energy. Thank you to whoever took the photo. Nick Cunliffe perhaps

Alan has opened more doors than I could have imagined back then, among the satisfying remains of our Calmac breakfast. Each late Autumn an email string will open: “St Kilda?”, with a carefully thought-out outline plan. So: twice to St Kilda, the Monarch Islands, round Islay, Mingulay, the Scottish north coast. That’s just a few. Wonderful places, wonderful people. Thank you Alan. It has been a great gift.

Alan in his snowy element, on some crag. Photo from his website.

Alan, Pen, Andy at the start of the Garvellachs glamour rocks. Photo by Neil.

So, ten years later, August 2024 and here we are coasting down the pink gold cliffs of the Garvellachs. It’s been top of my wish list for ten years and now we have made it. The Garvellachs are an archipelago of four islands tumbling like a curvy dragon's back from tiny Dun Chonaill at the northern end to Eileach an Naoimh at the southern. A charismatic place. At the north end a tiny thirteenth century castle on a pinnacle of rock, at the south, a monastery founded in the sixth century.

On Eileach an Naoimh is something special. An exposed rock recently awarded a coveted Golden Spike a GBSSP. Briefly, the rock is part of the Port Askaig Formation, composed of layers of rock up to 1.1km thick, laid down between 662 to 720 million years ago during the first of two global freezes thought to have triggered the development of complex, multicellular life on our planet. Here on the Garvellachs it is exposed, it has not been scoured away by glacial action. Uniquely the rock is showing our world's transition from a warm tropical environment into a frozen world, "Snowball Earth".

We paddlers are coasting along the west side, where the cliffs drop 100 metres sheer into the sea. We are strung out so close to the base of the cliffs that to take in their grandeur you must lie back on your deck. This I am doing, looking up at eagles floating out on the thermals from their rock cleft nests. Beside me waves heave onto the rocks falling apart in a white crush. I can soak up the waves energy, I can smell the ozone.

This time “we” are Alan, Andy Ravenshill, and Nick Hall, Amy and Neil and me. Alan, Andy and Nick have all “worked on the hill” all their lives. They are mountaineers. They are hugely skilled, used to making tough decisions. I am, as ever, appreciative of their company. And Amy and Neil are family, what more could I ask. I have more confidence in myself now than I did ten years ago. I am no longer a beginner. Every Spring I train so I am fit enough to pull my own weight. I know how to look after myself or a friend in need. I trust my own judgement and skills. But I hold these guys in huge respect and feel so lucky to be with them.

Landing at Eileach an Naoimh. Photo by Andy

Nick takes us into a modest inlet at the base of Eileach an Naoimh. You could easily pass it by. It doesn’t look like a landing spot for anything bigger than a kayak but this is where Brendan the Navigator would have pulled in his curagh in the sixth century. A narrow triangle of pebble beach. Nothing much. We have to take turns to land and clear a space for the next boat.

Unloading. Heads down Neil, Amy, Alan and Pen. Nick's done. Photo by Andy

We’re heads down unloading our boats’ hatches into fat blue IKEA bags. There’s not much room with six kayaks pulled up. It’s a fair old carry. It takes me four trips. Head down, stomping up I notice a big crop of watercress, then spearmint and water mint on the sides of the stream’s muddy banks and among big red boulders. There are fat stands of Flag Iris and fairground pink Loosestrife. It’s all stitched together with Lady’s Bedstraw. The smell of the sea has been in my senses all day, slightly antiseptic, sterile. This is different, a tang of crushed mint, grass, sharp, green, sweet water.

At the top of the slope is an open area of roughly mown grass. Despite everything Historic Scotland have been here. There’s even a Visitor’s Board, so unexpected in this unpeopled place. Visitor signs are great, but somehow they diminish the shock and awe of where we are, touching a culture that is so unimaginably different. The sign board has it all packaged up. It’s an ancient monument. All questions can be answered. Except they can’t.

Here is the walled outline of Saint Brendan’s Monastery, started in 542CE, a place of pilgrimage and burial until the late middle ages, abandoned to the Vikings in the 11th century. There’s a diagram of it. Despite the information board it’s hard to make sense of, to “read”. The buildings and boundaries of each era have been built on top of each other. The Vikings smashed down parts of the Monastery but not, for some reason, the magnificent bee hive cells. The farm plundered more building stone from the monastery and no doubt appreciated their predecessor’s eye for good pasture. The farm, the church, the souterrain, the burial ground and the monastery are all telling their story, but I can’t decipher it.

Inula Helenica on Eilean an Naoimh. Photo by Pen

But, in-your-face and evocative is a brash stab of yellow daisies, fine rayed petals around a deep pin cushion heart held 5 foot high. So exotic, so unexpected, so extraordinarily unlikely here in the Outer Hebrides. Inula Helenica. This plant originated in the Mediterranean. This plant is living proof that the monks were here.

The monks learnt their herbs, they grew their apothecary on the teaching of Disciordes. They revered Inula as a treatment for digestion and chest ailments. The thick fleshy roots were sliced into narrow discs and preserved in honey as cough sweets. Inula contains, of course, inulin. Disciordes knew this and the early Irish monks knew this through him. Inula is a survivor. If you got bored of it and dug it out it would cheekily self seed. From my garden Inula Magnifica has spread happily into damp stream banks and distant fields from whence it makes its presence loudly obvious.

According to the keepers of the monastic garden at MOMA in New York “there is evidence that Inula was a staple of Monastic diet in early Medieval Ireland.” And here it is, an astonishing survivor, evidence beyond any signboard, that the Celtic Saints were here, they cultivated the land.

Eyebright, plantain, wild strawberry and more, Photo by Pen

Andy has already got his tent up and a first brew going. He calls over “Have you noticed the eyebright? On the bank there?” The raised bank below the burial ground is embroidered with milky blue stars of eyebright, marbled celandine and sky blue harebells. Wild sorrel and the soft rosettes of primroses make up a green ground for the flowers. The good drainage offered by the bank has allowed several varieties of wild thyme to thrive. This bank would be an achievement more than worthy of a gold medal at Chelsea.

By the way, “a decoction of eyebright”, thanks to Disciordes, was used from the earliest times, to relieve tired and bloodshot eyes. I remember reading of its presence being noted as a marker plant for old monastic sites and healing wells. Iris was important for the monks as a dye for their robes.

Eyebright and Harebells, photo by Pen

Alan and Nick have already got their tents up in a little triangle of long grass and meadow-ant towers. Amy and Neil are perched at the top of the mown area and Alan is tucked neatly into the old chapel walls. As usual I’m still wandering about. As usual I'm dazed and confused.

To clear my head I take a walk up the bank to a place known as Eithne’s Seat. I’m looking out over the last scattered islets of the Garvellachs, Colonsay and the Paps of Jura. The sky is soft and silky. Washed out blues and pinks over a quiet sea.

Sunset from Eithne's seat. Thanks for photo from Andy

Eithne, Saint Eithne, was Saint Columba’s Mum. He was way later than Brendan. How did she get to be here? And why? And when she sat here how did she feel about not being able to see her home, Ireland? I feel a growing disgruntlement and confusion. I have so many unanswered questions. Quite simply, why did any of them come, and how?

The signboard shows half a dozen fat little monks stuffed into a tubby, pudding basin shaped boat with a keel to the bows and a steerboard at the stern. They’re all smiling like anything but the signboard, quoting from St Brendan’s "Navigatio", says they sailed “over the wave voice of the strong maned sea and over the storm of the green sided waves and over the mouths of the marvelous awful bitter ocean” to find this place.

St Brendan in a nutshell

But I don’t believe it. The journey is not so long but it is fickle and turbulent. That boat wouldn’t get them anywhere and, stuffed in like that they wouldn’t have been chubby and smiling. The journey was a serious, dangerous undertaking. And, if they were missionaries why would they come here? There was surely next to no-one to convert on Eileach an Naoimh.

I am trying to make sense of 6th century Irish Christianity in the context of my own 1950s Church of England background. My Father was comfortably an atheist. It mattered to my Mother that we were brought up in the Church. She was a believer though I was never sure what it was that she believed. We went to Church every Sunday. My cousin Jeanie and I read “Scripture Notes” and the Bible every night.

Our parish church was described as pretty by Pevsner. Perhaps so but it was also cold and dank. It smelt thickly of mould. The prayer books were a scuttle of silverfish. The dismal light from a few 40 watt lightbulbs hardly touched the side pews. The congregation would be the Reverend Mercer, me and Mum, two fine old ladies, Mrs Phillimore and Mrs Harris to whom we gave a lift. Sometimes the congregation was more than amply increased by Mrs Mercer. My goodness she could belt out those hymns, always slightly ahead of the organist and completely off key. During the sermon the organist would fetch a small bottle of holy water out from under his cassock, unfold a tabloid Sunday newspaper and relax into it. Reverend Mercer delivered the service in a pained low mumble. His sermons turned on dry theological points of order. He gave off a grey air of disappointment and slight irritation.

The religious world of 1950s England. Margaret Tarrant

My Common Prayerbook was blue cloth bound and inscribed on the inside front cover with “”Penelope Godber. With love from Mummy. Palm Sunday 1959.” It had everything I needed to know from “Table of Rules of the Moveable and Immoveable Feasts” to “A Commination, or denouncing of God’s Anger against Sinners” to special hymns for Missions Overseas. All useful stuff for a 9 year old.

These weighty matters were interleaved with illustrations by Margaret Tarrant. Arch Angels, small children and Jesus himself were always paley white with milky skin and honeyed curls. My favourite, much stroked and admired was the best saint of all, Saint Francis. His outstretched arms were crowded with little birds and beasts and squirrels whilst bunnies and deer and foxes nestled together peaceably at his feet. Now that was a miracle obvious to any country child.

On the way home from Matins the pagan congregation of the Green Man pub flowed vigorously out into the street, considerably louder and larger than ours in church. Mrs Phillimore and Mrs Harris tut tutted in the back of the car. Were these the sinners the bible spoke of? Ribald laughter rose in great waves from the pagans as we passed by. I clutched my Common Prayerbook ever so tight and vowed to pray for their souls. But I also thought they were having a lot more fun than us.

Many years later someone told me they were actually laughing at my Dad’s choice of cars. The established order of that time was that sensible people, if posh, had a Rover, otherwise a Ford Popular. My dear Dad tried a Rover and found it boring. A cream Nash Rambler with whitewalled tyres was followed by a two-tone pink and grey Citroen DS, the first in Britain and, when he moved to Jersey, temple to ostentatious wealth, a second hand, soft topped Fiat 500. Soft topped so my dog Freddy could sit in the back, paws on Dad’s shoulders sniffing the breeze with his furry ears flying out behind.

The Reverend Mercer and the Book of Common Prayer was my childhood model of Christianity. Mercer would definitely not have stepped foot in that pudding basin boat, or any other boat. Saints, according to the Mercer Church, were anyway rather vulgar. Inclined to showing off they had to die horribly and perform miracles. They had at least to be heroically good. Them’s the Rules.

Strangely my cousin Jeannie and I were rather taken by Sainthood. We had exciting plans to dedicate our lives to Jesus. Before moving on to other things we spent at least two school holidays zealously planning how we could achieve our goal of martyrdom. We thought we could take a step forward by joining the choir. Our hopes were dashed by the Reverend M. He showed ill-concealed repulsion for the idea. Girls, he decreed, could not be in the choir. Nor could they be saints. We would have to find alternative careers. By the next holidays we'd both discovered Cliff Richard, a poor substitute I would agree.

Saintly visions for Jeanie and me! Thanks to Margaret Tarrant

So here I sat on Eithne’s seat with very little feeling for why Brendan, and then Columba had come here and what they were here for. I want to understand who Brendan, Columba and Eithne were and I can’t get anywhere near them.

I am asking myself the same question I’d been asking everyone the same question all summer. How and why did saints come to the islands? Most people, like me, had formed answers from their own understanding of the world, informed by their beliefs and by their personalities. A tourist on Iona had told me it was because “they were so spiritual”. That means nothing to me. Amy said “How would I know? I don’t know anything about Christianity.” Unlike my Mum I didn’t take my children to church. Alan’s answer was: “For adventure! They were the great adventurers of their times.” And I’m sure he was right, like Alan, Brendan was an adventurer, an explorer, a traveler. But in what sense was he a saint or a missionary? Certainly not in the Reverend Mercer’s sense.

The smell of everyone’s supper cooking and with it the clink of beer bottles fetched me down to the tents. Over a wee nip Nick held forth on how the land had been cultivated and the shame of the land being left to go back to the wild. Like a fool I say something half-baked about re-wilding and am knocked back by a kindly gale of Bunahabin. Nick is an intellectual juggernaut. He doesn’t do half baked. That’s the first thing I ever noticed about him apart from his wooden paddle and speedy paddling.

It was not till weeks later that I realised Nick was the one I should be asking. I emailed him the question that I had been asking everyone all summer. Suddenly, thanks to Nick, I was on track. Most of all, he got the question: not “why would I, Nick have done it” but why did they do it?

Nick’s email in reply to my question was headed: “E. G. Bowen: Britain and the western seaways. London: Thames and Hudson, 1972. | Antiquity | Cambridge Core”. This book, he said, would give me a starting point. E. G. Bowen, Professor of Geography and Anthropology at Aberystwyth is “an authority on the spread of Christianity and Medieval trade.”

Happy reading, enough for a whole winter, thanks to Nick. Photo by Pen

Many more books that Nick recommended have acted as signposts along the way. I had embarked on a winter journey that has taken me from 2025 backwards to 280,000BCE, from first humans, probably, through the Mesolithic age and the first boats dug out from logs, onwards to 1,300BCE the Welsh Caergwle boat and the Irish golden Broughter boat. The “Extraordinary Journey of Pytheas the Greek introduced me to Pentecomer and Tiremes of the 4th century BCE, and Tim Severin, historian and adventurer, brought Brendan, his currach and his journey convincingly to life. The sixth century West Coast Irish version of Christianity made Eileach an Naoimh come vivividly to life.

In a way it was fortuitous that I was ill from December 27th until late March. It gave me time to read Nick’s books and begin to answer the questions that were nagging me through much of the previous year and which confronted me as I sat grumpily on Eithne’s seat. It has been a fine winter journey. A journey that has challenged my understanding of the world.

I haven’t become a historian but I have come to understand more of the world that Brendan, Eithne and Columcille lived in and the particular form of Christianity that informed them. I’ve had to upend my own world view which definitely becomes harder with age. But exciting. I’ve learnt to count backwards like the Greeks (think about that). To use the terms BCE, Before the Common Era and CE, the Common Era rather than AD and BC which date history by the birth of a religious figure not deified by half the human race.

I knew that Ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians were developing the tools of science when we were still cutting flint axes but still it was a mental battle to accept that technology doesn’t necessarily progress in a forward direction. We commonly date eras by progressive technologies: Stone, Iron, Bronze. It was hard to accommodate the idea that the Greeks had developed the Pentecomer, a fantastically manoeuvrable, sophisticated boat nearly a thousand years before the Currach and that both boats were in use concurrently.

Bowen, in “Britain and the Western Seaways” and Cunliffe in “Facing the Ocean”, show that the sea did not divide us, it connected us. It was the way that ideas, technologies and goods travelled. Once the great melt of the last Ice Age had flooded the land bridge that connected Britain to Continental Europe our ancestors began to exploit the Western Seaways. Cunliffe describes it as “a dramatic re-ordering during which transformation a distinctive Atlantic culture emerged.” That’s us. That’s our ancestors, and Eithne’s.

Mesolithic axe heads from Shetland Museum. Do we find these beautiful because our ancestors prized them?

Bowen and Cunliffe evidence this in carefully plotted maps showing, for example, the distribution of Mesolithic axe heads produced in Raithlin Island, NE Ireland and discovered in sites in Brittany, S England, the Isle of Man and places north through Orkney and Shetland. Both Historians chart the spread of, for example, passage tombs and gallery graves that fringe the same Atlantic edge.

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin. Just read it, it won't take you long. Severin built a currach as close as possible to St Brendan's and sailed it to Nova Scotia, proving that Saint Brendan's journey was feasible.

Like Alan I am sure that some of our ancestors were driven by adventure and curiosity. We paddle to find out what is round the next corner. Brendan, looking for the promised land, the island of the saints, was surely an adventurer.

Nick finished his first email with “It could be said that you are replicating and rediscovering the world of the navigators of skin boats, and evidence of a lost society, as islands return to their natural state.” Now that’s nice. I would like to call myself, and my companions, Peregrini. We can be like the three Irish Saints that washed up on a Cornish shore who, when asked where they were bound for, answered “Who knows? Where God” and in my case the wind, “takes us.”

Peregrini pals, Andy, Nick, Pen, Alan. Photo by Neil or Amy

Of all the islands I slept on in 2024 I would like to go back to Eileach an Naoimh. I would like to go back and sit in the grass at St Eithne’s special place. The view that I would look out over is completely unchanged from the view that Eithne looked out over. Imagine a quiet pearly sea, just a scrabble of islands and then the Firth of Lorn and the wide open space of the sea all the way to Jura and beyond until the sea merges into the sky.

Sunset over the Garvellachs. Photo thanks to the Geology Society of Scotland

Eithne and I could sit together, two women, companiable. And I would ask her my first question: how did you get here Saint Eithne? She would answer, as chatty as you like, “Well in a curach of course, how else? Like Saint Brendan of course, and later my own dear Columcille, the one you call Columba, after Adomnan and the Latin you know. Adomnan wrote my Colum’s story and of course he did get some of it right but he was, well you know, a hundred years on, a bit stretched. Miracles and the like. They had a taste for them in Adomnan’s day. So yes, I came to Iona and then to here in a currach, 12 monks with me and every one of them a Saint because we set forth where God’s wind would take us”.

“But Eithne” I would ask her, “Some say Saint Brendan the Navigator was just a legend, that he never made that journey, that he never reached the Isle of the Blessed.” “The place you call Nova Scotia? Well what do they know? The trouble with historians is they have to get things right and that's impossible over so many years. They can't just sit and chat as we do. Of course Brendan got there. And what a journey. He showed us all the way.

I loved my journeys, short as they were. The currach creaked and moved beneath me. It swayed and rolled with the sea. The great creatures that live in the ocean depths came all around us to share their stories. We rode great walls of green waves with the stars and God’s angels to guide us. I had no fear because I was in God’s hands and taken by the breath of his lungs.”

“You know he found it. Brendan found the Promised Land. “He settled abroad with sail spread out and set to wander wheresoever the wind would will.” That’s how the story goes, and of course many stories were told of him “fed and dressed by God’s own larder.” Brendan wasn’t the first to have a tale to tell. There was Saint Egreria. She wrote her own story, “The Peregrinatio Egreria” in the year of our Lord 385. She set forth from Galicia and travelled to the Holy Land. Now she taught us that going forth doesn’t bring you closer to Jesus for He is everywhere. Though of course for you, as a Heathen, that might not be the case.”

“Why did you leave Ireland for Iona?” I would ask. “Well Colum, he was my boy, a Saint as God willed but my boy. He needed me. He needed me despite all his fame and wisdom, my little Crimthann. For that was his first name you know: my little fox cub. Iona was the place to be. So many people came to share ideas, their skills and their art. There was so much coming and going and chat so I came here in the end, as my quiet place. We all did, but it was Brendan who came here first.”

The famous beehive cells on Eileach an Naoimh. Photo by Canmore

“Brendan started the monks here and then he moved on. He was a traveller, you know. A true Peregrinatus. A White Saint he was indeed. He went forth into the wilderness, following the teaching of the Desert Fathers. Now Colum was also a White Saint, leaving his home and going into exile for God but once he reached Iona, which was given to him by our relative Conall mac Comgaill, King of Dalraida, then he stopped. It was my Colum’s gift to listen and teach and learn. It was his gift to draw people to him. That was what he was there for. Everyone came to Iona to share and to learn. It became a centre of learning for the whole world, not just Dalraida. All the seaways met there.”

“You must remember we had always taken teachings from the sea, from listening to travellers. We listened and learnt from the Eastern travellers, from the Pelaganists, the Druids and the Picts. But the word came to us first from the Desert Fathers and then from our dear brethren in Armorica. We listen, we share teaching and learning. Rome thought we were heretics because of it. They did like order and obedience you know. But there’s more than one way and God blesses them all.”

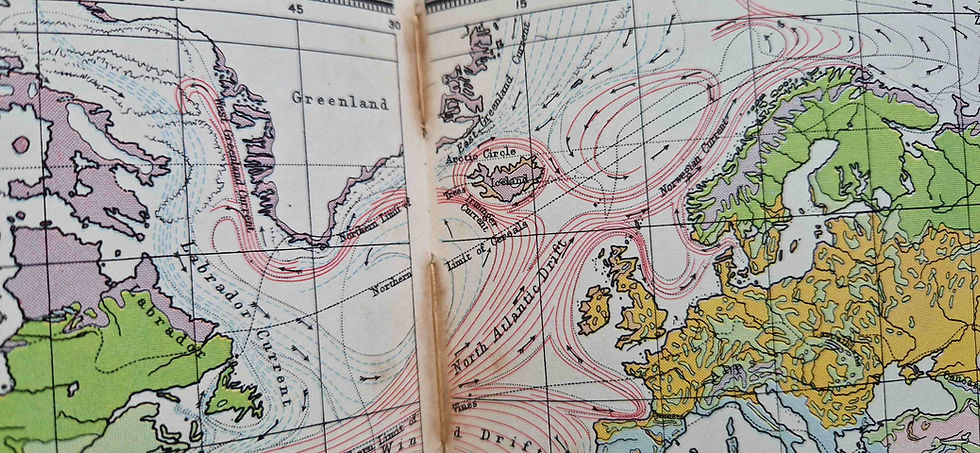

My old school Phillips Atlas showed the same ocean currents that Brendan followed

I had worried that she would be lonely buried so far from home? After all very few people come here. So I ask her "Don’t you get lonely?” “Ah no,” she would answer “Put your mind at rest. This is my home. My home follows the trade winds all the way to what you call the Faroes, on through the lands of icy waters, on to the Promised Land and then back to Galicia, Armorica and Ireland, back to Clontarf. And all of the Saints are free to meet and share our thoughts. We aren’t tied to the earth like you are my dear. Sometimes the air stretches a little thin, but this is my home, my heartland.”

“And now” she says, “I have a question to ask of you. How much did you learn about my sister Saint Tecla when you slept on her island, Chapel Rock below your Severn Bridge. I always love visiting her to watch that magnificent bridge they've built there. Ah but the mud! And the speed of that water! Did you stop to wonder why Tecla, a Breton Princess would choose such a desolate barren rock where the salt water rushes to meet the brown river twice a day? Well now you know: this was the teaching of the Desert Fathers. She set out to be a Green Saint, a hermit living all alone, fed only by her pilgrims straggling out across the mud and shingle when the tide allowed them. But of course her destiny was to become a Red Saint. All alone on her desolate rock her fate was to be murdered by sea pirates, a blood martyr to our Lord.”

So I begin to comprehend that "my" Christianity, Reverend Mercer’s Christianity, 1950’s C of E derived from Rome under Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century. It was in many important ways quite different from Eithne’s Christianity, the early Christian Church of Ireland, influenced and inspired by “The Desert Fathers”. Brendan, Eithne and Columba's teaching came from the Middle East along the same sea routes that Bowen has described, trade routes of the Middle East and the Mediterranean and Aegean coast.

“You’re pretty well read Eithne,” I would venture. “Well,” she would answer turning to me with a bit of an eyebright twinkle, “what else would I be doing? I’m pretty well connected. I like a good read. And I can speak in all tongues too. I listen in to all you visitors too. Not that there are all that many of them here, God be praised, but I can always skip over to Clontarf. Or anywhere else.”

“And, while we’re at it, your friend Nick. Now he is quite right! It is dreadful that they took the cows and the sheep off. The island is disappearing into the bracken and the heather! Nick is right to say you are losing the skills we strove so hard for.

We chose good land you know and we worked it well. No wonder the farmer from Eilean dubh Mor carried on with the grazing after those Godless Norse men left. We have good water for the cows here, fine grazing. All wasted! And it’s more than that. You can’t walk the old ways anymore, the paths are all choked up, strangled in brambles and bracken. Of course I can go anywhere but you can’t. The old ways are lost! You should have seen the flowers and the herbs we had back then. Re-wilding? Why would you do that on the Eileach? Haven’t you got enough wildness on the rest of the Garvellachs? Young Nick is a true Bard. Anyone can see that! Pin back your ears and listen child!”

After a bit of a huff she settles down again and stretches out to admire her feet, a tidy pair of winged Nike trainers peeping out from under her robes. “Of course I can go anywhere even without these, however high the bracken” she declares with just a hint of pride. And then, with just a swish of Irish tweed, she’s gone.

Brendan's gulley with Bard. Photo by Andy.

And so we sit here, the Bard and the rest of us Peregrini. We’re sitting where Brendan and his Saints first pulled up their Currach. In the legends a Saint will then come down to greet them and welcome them onto the island. Only then can they set foot on the island and go up to drink from the stream. If any of them goes before they are greeted they will suffer for it.

We have no such formalities, coming or going. We are going to launch our kayaks one at a time back down the narrow gulley and make for Easedale. Nick is way out ahead of us, miles ahead, slicing the water with his trusty wooden paddle.

See you at the pub, Bard,

Nick on a mission to save the last pub table for the rest of us. Photo by Neil.

Nick's book list and beyond

By the way, the books my local library didn't have I was able to find very cheaply second hand at Oxfam Unlimited online and Abe Books

Britain and the Western Seaways, E G Bowen, Thames and Huson

The Settlements of the Celtic Saints in Wales, E G Bowen. University of Wales Press

Facing the Ocean, Barry Cunliffe, OUP

The Extraordinary Journey of Pytheas the Greek, Barry Cunliffe, Penguin Books

The Brendan Voyage, Tim Severin, Cornerstone (and others)

The Voyage of Saint Brendan the Navigator, translated by Gerard McNamara in verse form

The Book of Kells, Bernard Meehan, Thames and Hudson

Life of St Columbus, Adoman, Penguin Classics

Disciordes on Pharmacy and Medicine, John M Riddle, Texas

A book of Herbs, Dawn Macleod, Garden Book Club

Culpepper's Complete Herbal and English Physician, Pitman Press

Some of our ancestors journeyed to find “Thule” the furthest North you could go, some to discover whether the world was truly dish shaped. Nick recommended Cunliffe’s reconstruction of Pytheas’s extraordinary journey. 2,300 years ago around 325BCE Pytheas travelled to trade in tin, amber and gold. In modern terms you could say that that was what he was funded for, but there is no doubt that what drove him to explore the lands north of his known world was intellectual curiosity. Pytheas travelled along the west coast of Brittania and beyond to the polar ice of the Arctic. He travelled to the limits of his known world.

https://archive.org/details/extraordinaryvoy00cunl

Fair winds for Colonsay:)

xSpike